Exceptional Prints: Andy Warhol

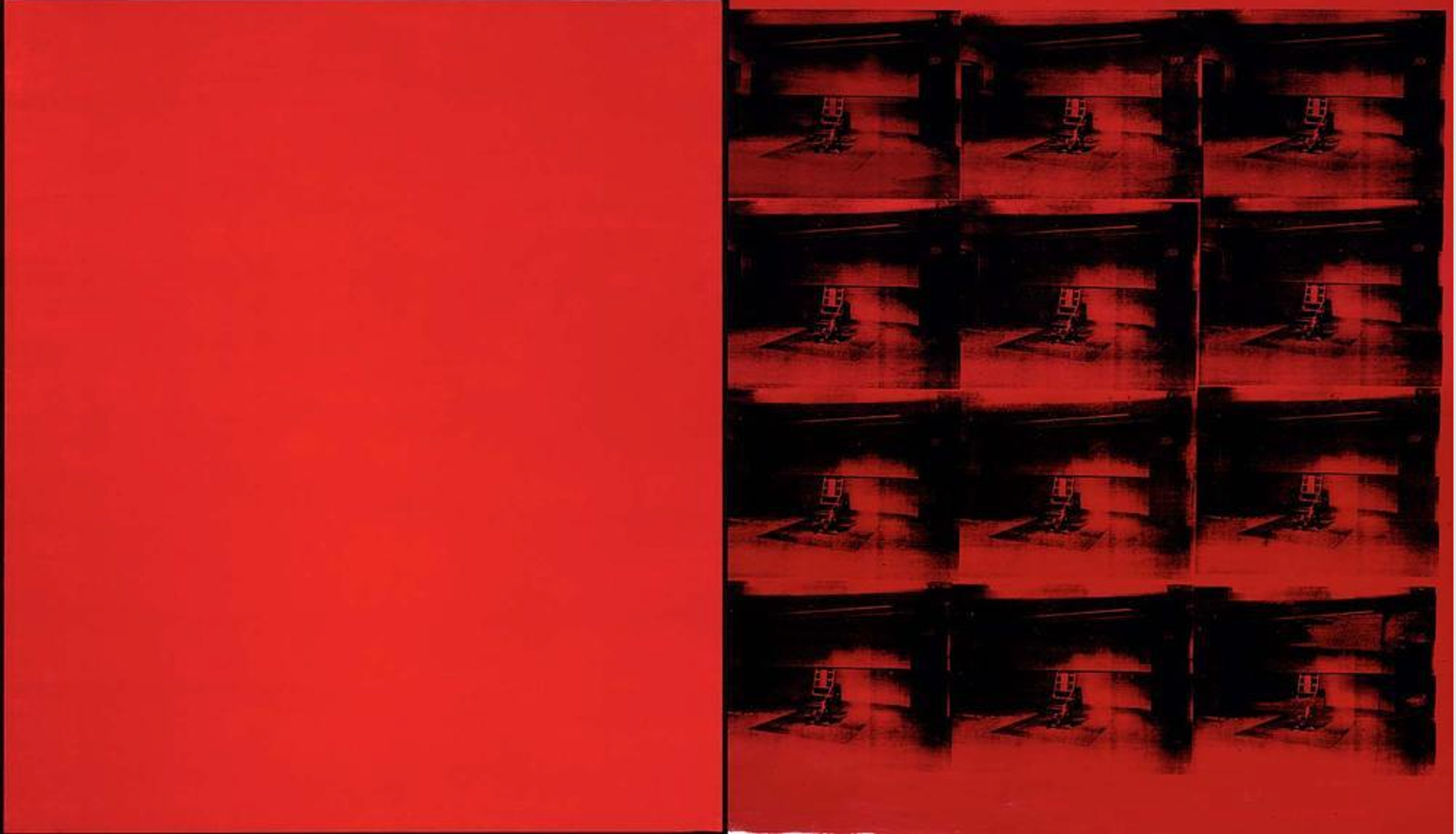

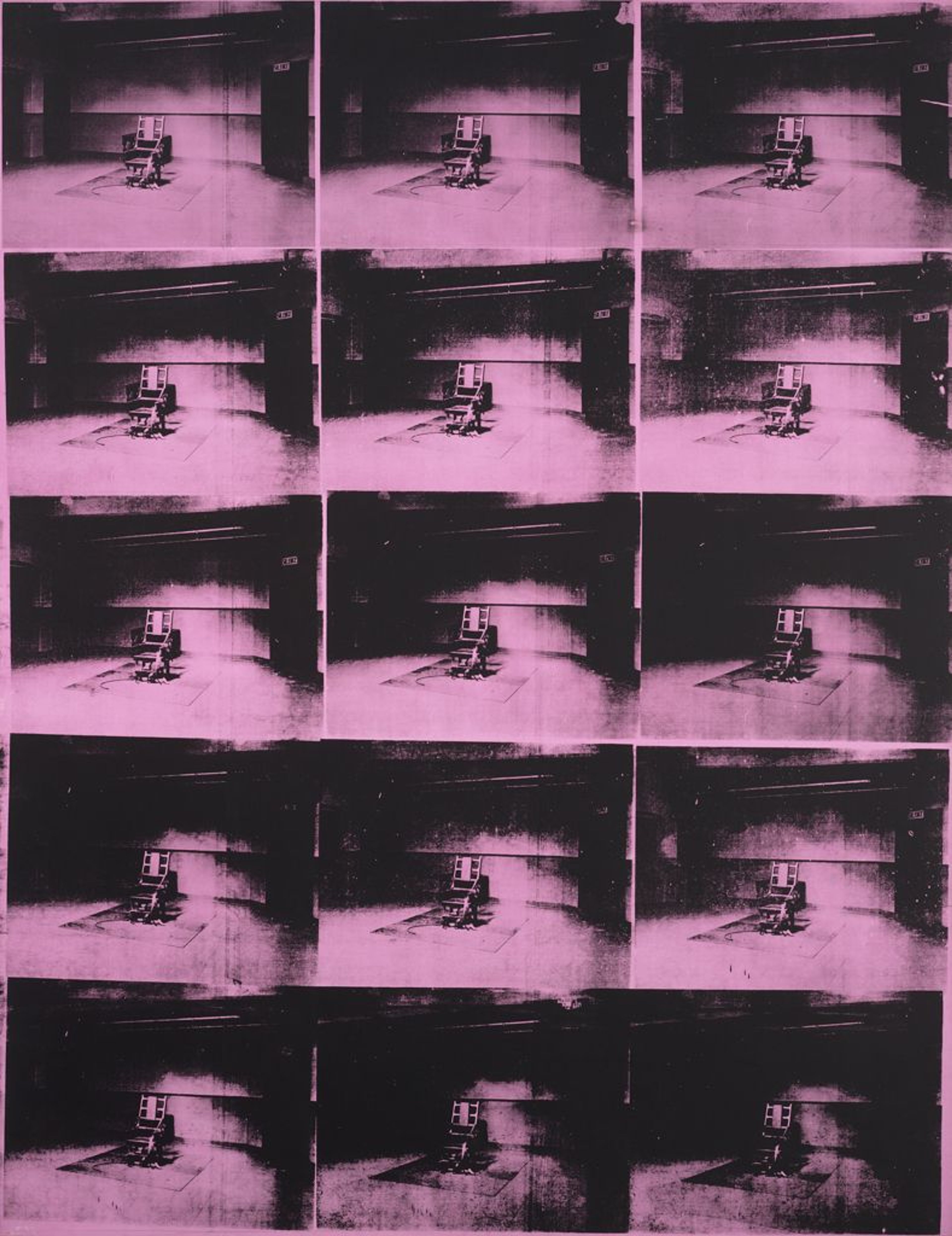

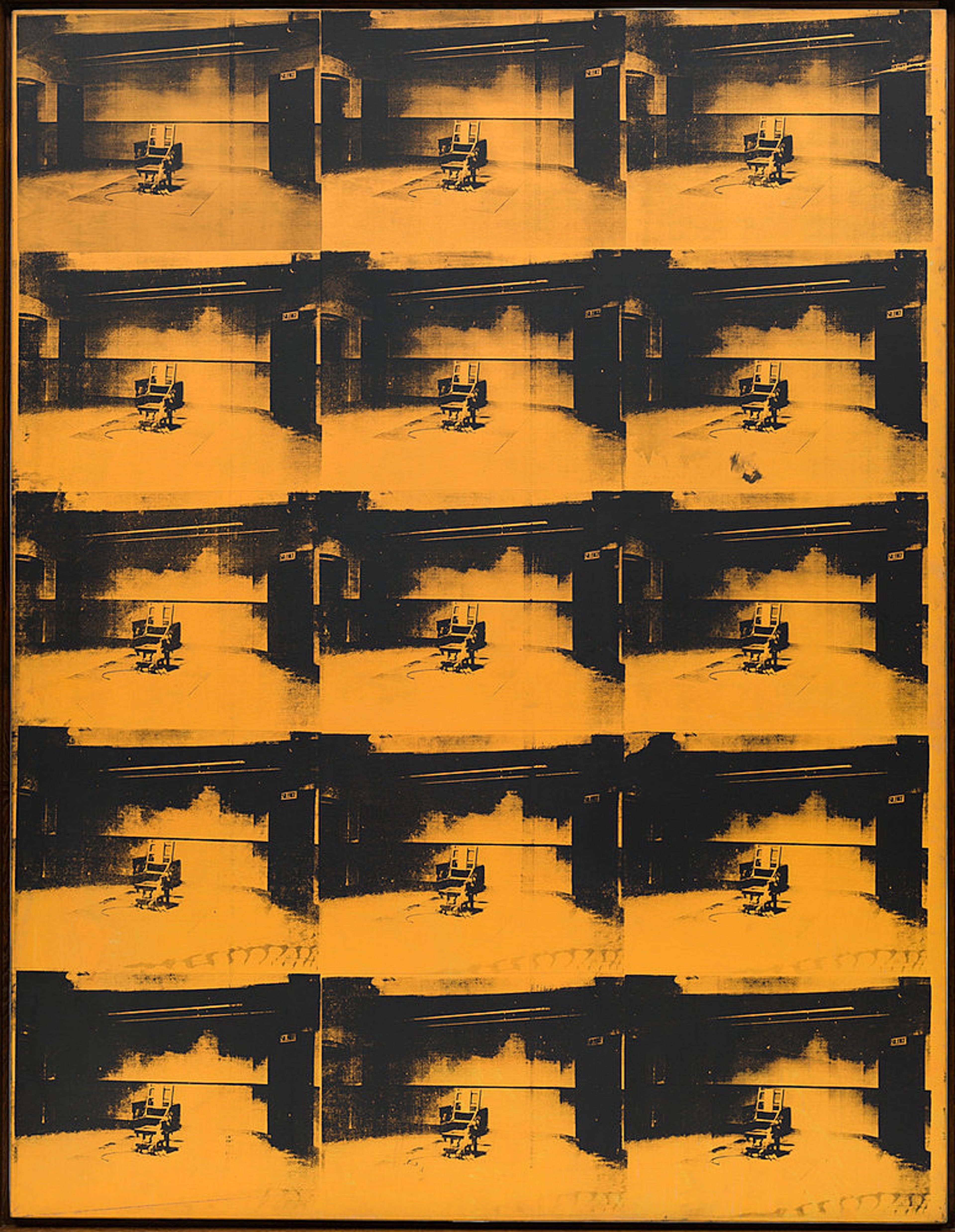

Electric Chair, 1971

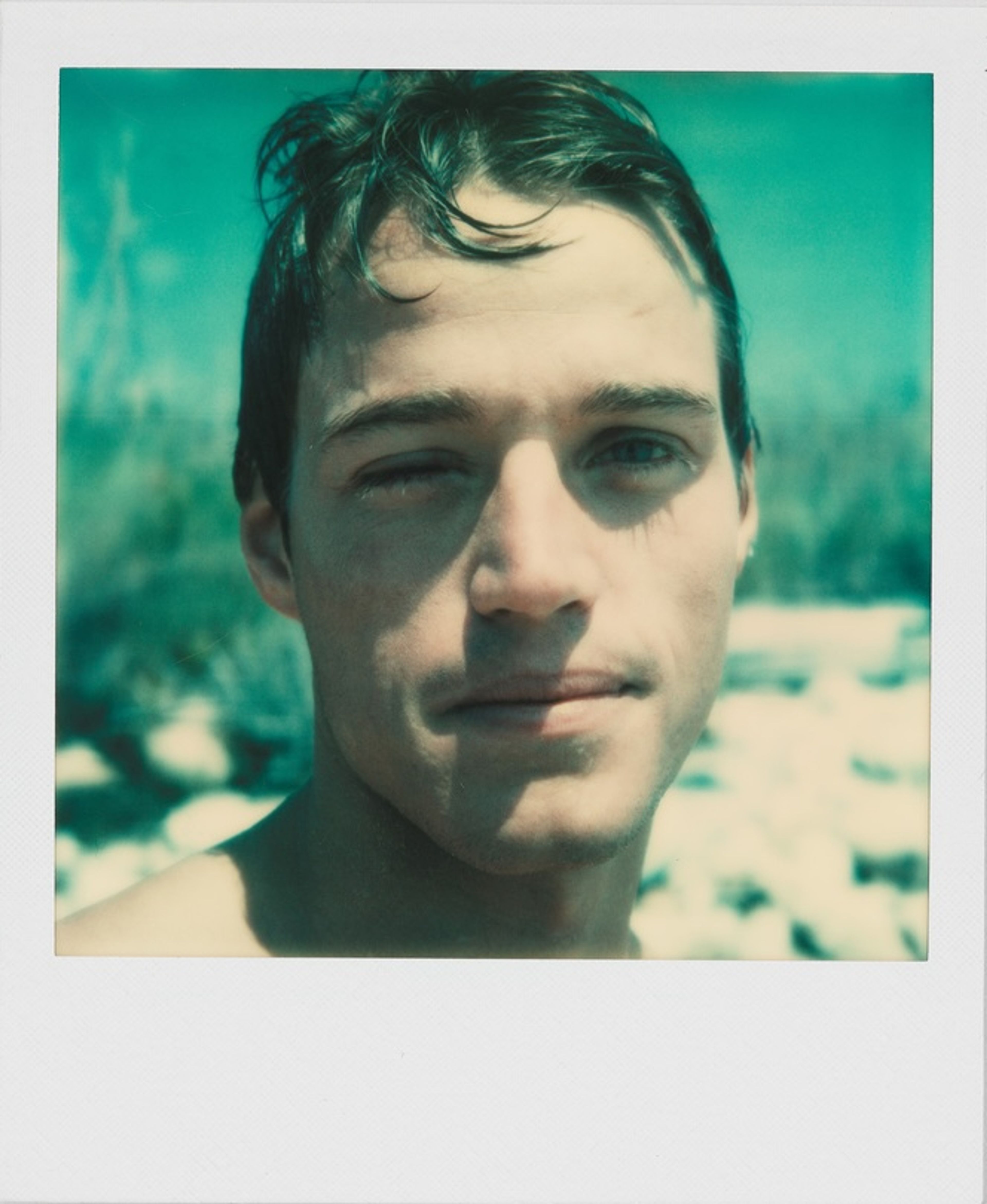

A polaroid of Jed Johnson by Andy Warhol, 1973. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

David Zwirner is pleased to feature a rare complete portfolio of Andy Warhol’s Electric Chair screenprints on the occasion of our Art Basel Miami presentation. Printed in 1971, this portfolio of ten prints features the seminal image of the death chamber at Sing Sing Prison from Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster series of the 1960s. This particular portfolio is distinguished for its superlative provenance. It was a gift from Warhol to the celebrated interior designer Jed Johnson (1948–1996), Warhol’s partner from 1968 to 1980. It has never before been offered for sale and remains in its original portfolio box.

Other full sets of this portfolio are held in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate, United Kingdom; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

The groundbreaking Death and Disaster series, begun in 1962, was a chilling indictment of the 1960s American public’s fixation on images of death. Over the course of the decade, Warhol continued to mine newspapers and magazines for documentation of suicides, assassinations, car crashes, and electric chairs, and screened them onto both canvas and paper. The electric chair would become one of his most recognizable motifs and one he would return to in several major paintings.

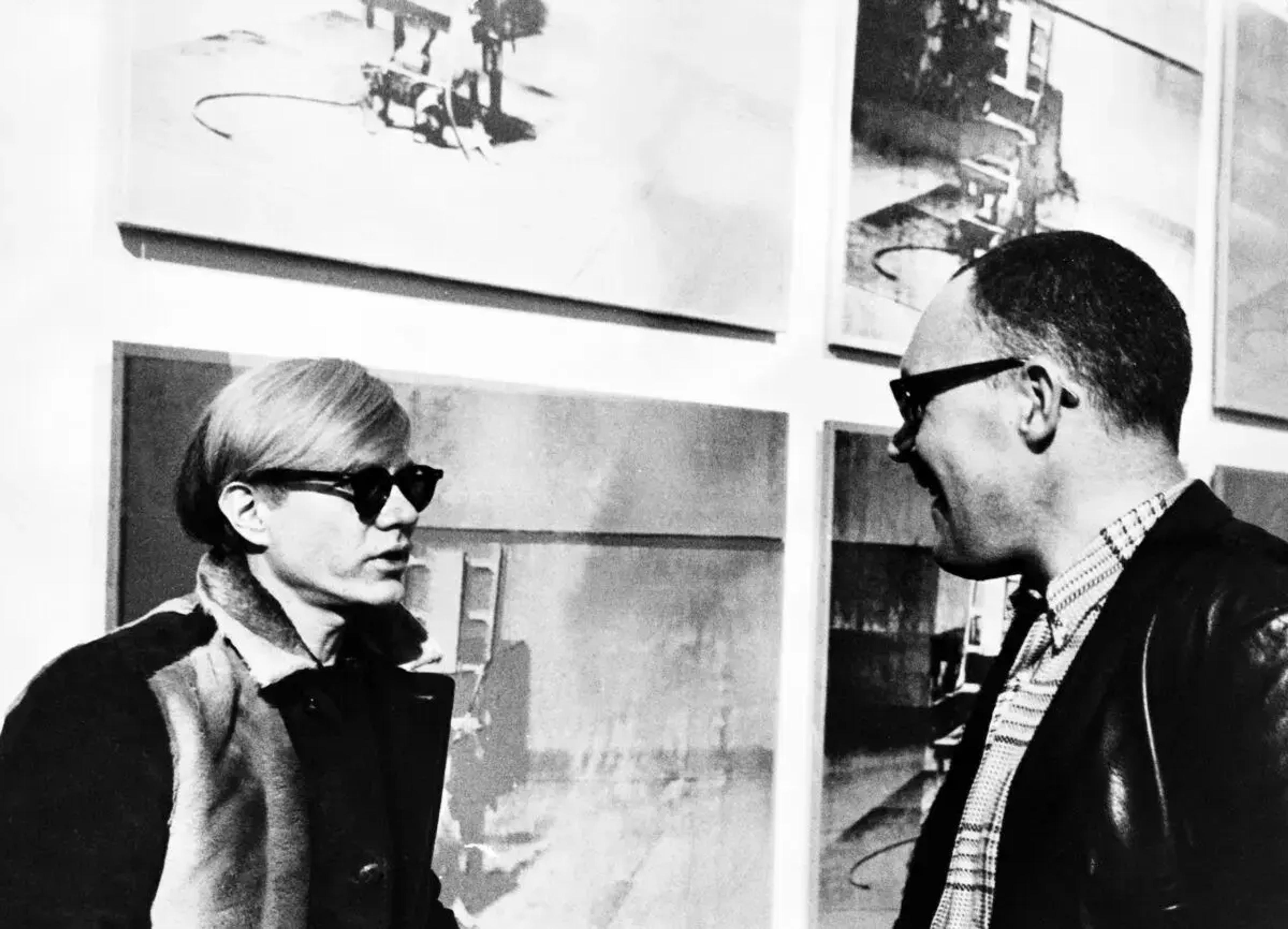

Andy Warhol and Jed Johnson together in New York, 1971. Photo by Gerald Malanga

Inquire about Electric Chair

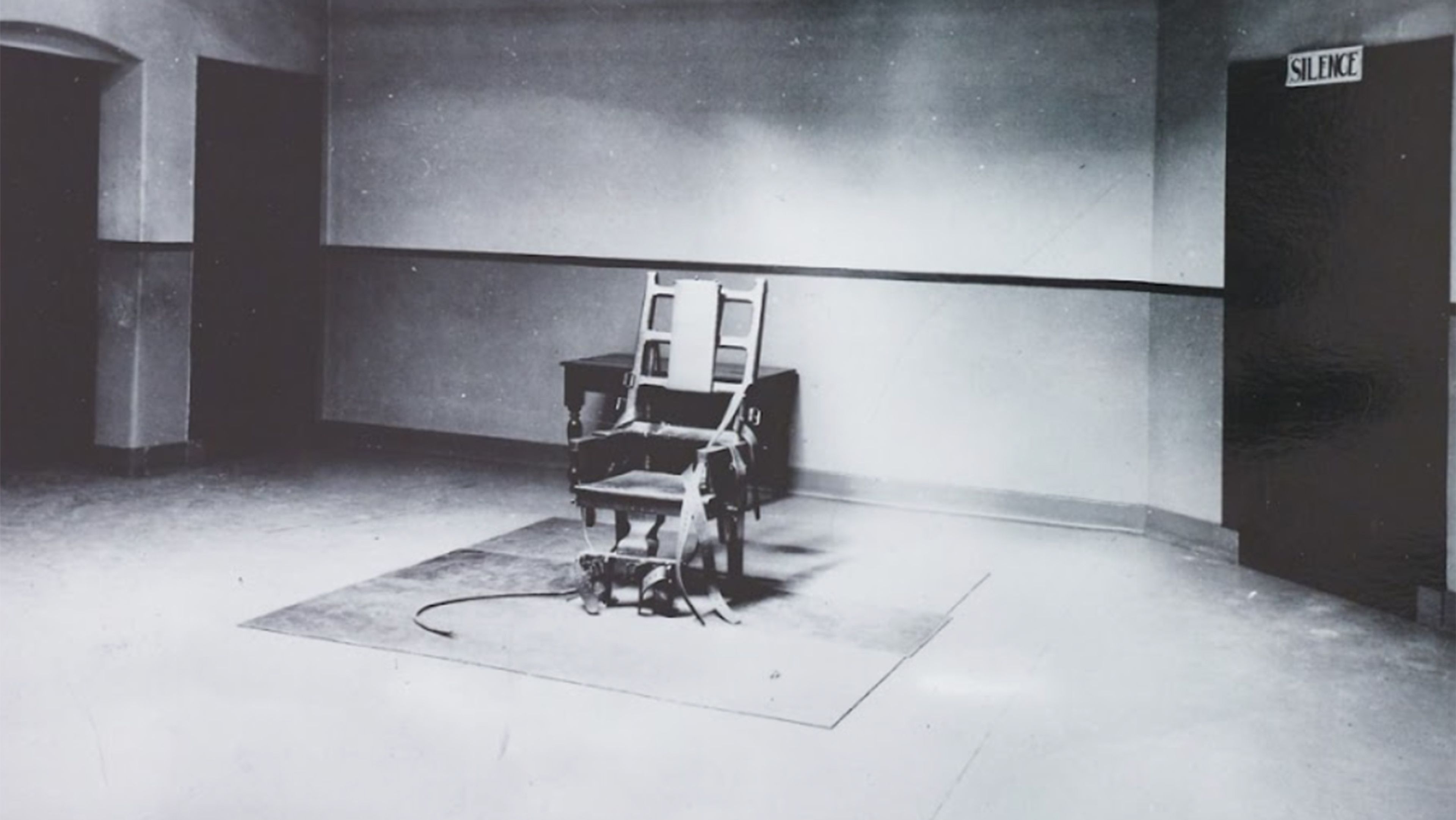

Press photograph of the death chamber at Sing Sing Prison in Ossining, New York, January 13, 1953

Uncropped source image for Warhol’s Electric Chair works

The Electric Chair works are unique among Warhol’s Death and Disaster series in that they do not depict violence itself. The image is framed to foreground the vacant chair, which acts as a surrogate for the human body it was designed to restrain.

Andy Warhol and Pontus Hultén with Electric Chair paintings installed in Warhol’s first major museum exhibition in Europe, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 1968. Photo by Nils-Göran Hökby

Warhol began his Death and Disaster series in 1962, and early works from this series were first intended to be shown not in the US, but in Europe at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris in 1964. Anticipating that the French intelligentsia might dismiss his first major presentation in Europe as trivial representations of consumer culture, Warhol elected to confront the violence of 1960s media culture with motifs of death destruction, and suicide.

Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1971 (detail)

Warhol experimented with multiple variations in the composition and color combinations during the proofing process. Certain details retain the immediacy of their production, a style that would come to define Warhol’s return to painting in the early 1970s.

“The procedural shift to an actual mechanical process—the silkscreen technique, used as one would use a brush—remains his most crucial breakthrough.”

—Donna De Salvo, curator

Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1971

Art Basel Miami Plus

Additional Works From This Year's Featured Artists

Inquire about prints and editions