The Guardian, interview by Eddy Frankel

2025

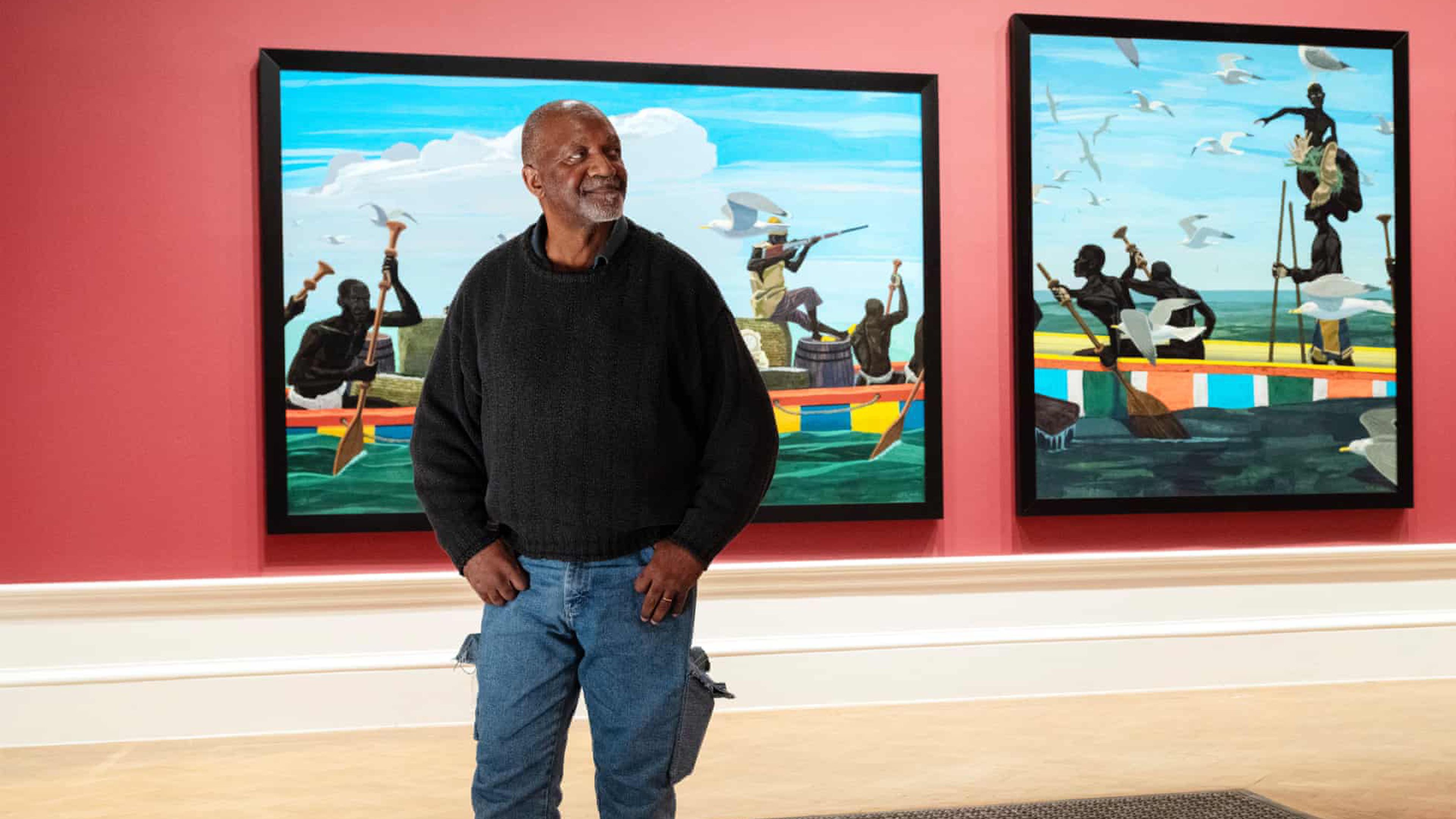

History weighs on Kerry James Marshall, though not all that heavily. When he talks about the hefty subjects of his art – from slavery to civil rights – he does so with a disarming, disquieting lightness. Maybe that’s because at almost 70 years old, and at the peak of his popularity, he’s seen it all. Marshall grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, just a few blocks away from where the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, a white supremacist attack that killed four young black girls, took place in 1963. When his family moved to Los Angeles, they ended up right in the middle of the 1965 Watts riots, a six-day uprising fuelled by growing racial tension in the poorest part of the city. All of this has undoubtedly fed into his journey to becoming arguably the US’s greatest living painter. Today, seated in the galleries of the Royal Academy in London, where his jaw-dropping, large-scale, colourful paintings are going on display for a major show, he reels off a list of traumatic, shocking events from his youth. Beatings, murders, injuries, robberies, “and that’s not even half of it,” he says with a smile, chuckling. “I came this way against the odds, given the time that I entered art school and the way people told you that you’re not supposed to do this kind of stuff,” he says. “That had no effect on my ambition, because I set my own goals. They don’t tell me what I’m supposed to like and what I’m not supposed to like. I don’t accept that.” From the start, Marshall’s vision has been knowingly defiant. The cultural environment he emerged into after graduating from art school in the late 1970s was one heading full bore into conceptualism, and still trying to deal with the afterglow of abstraction, pop and postmodernism. He ignored all of that, and chose instead a notably classical take on figuration. Yet what he did was startlingly modern: he used the language of classicism to elevate ordinary, everyday and – crucially – black subject matter to the level of Titian, David or Velázquez. Read more