Andra Ursuța: Retina Turner

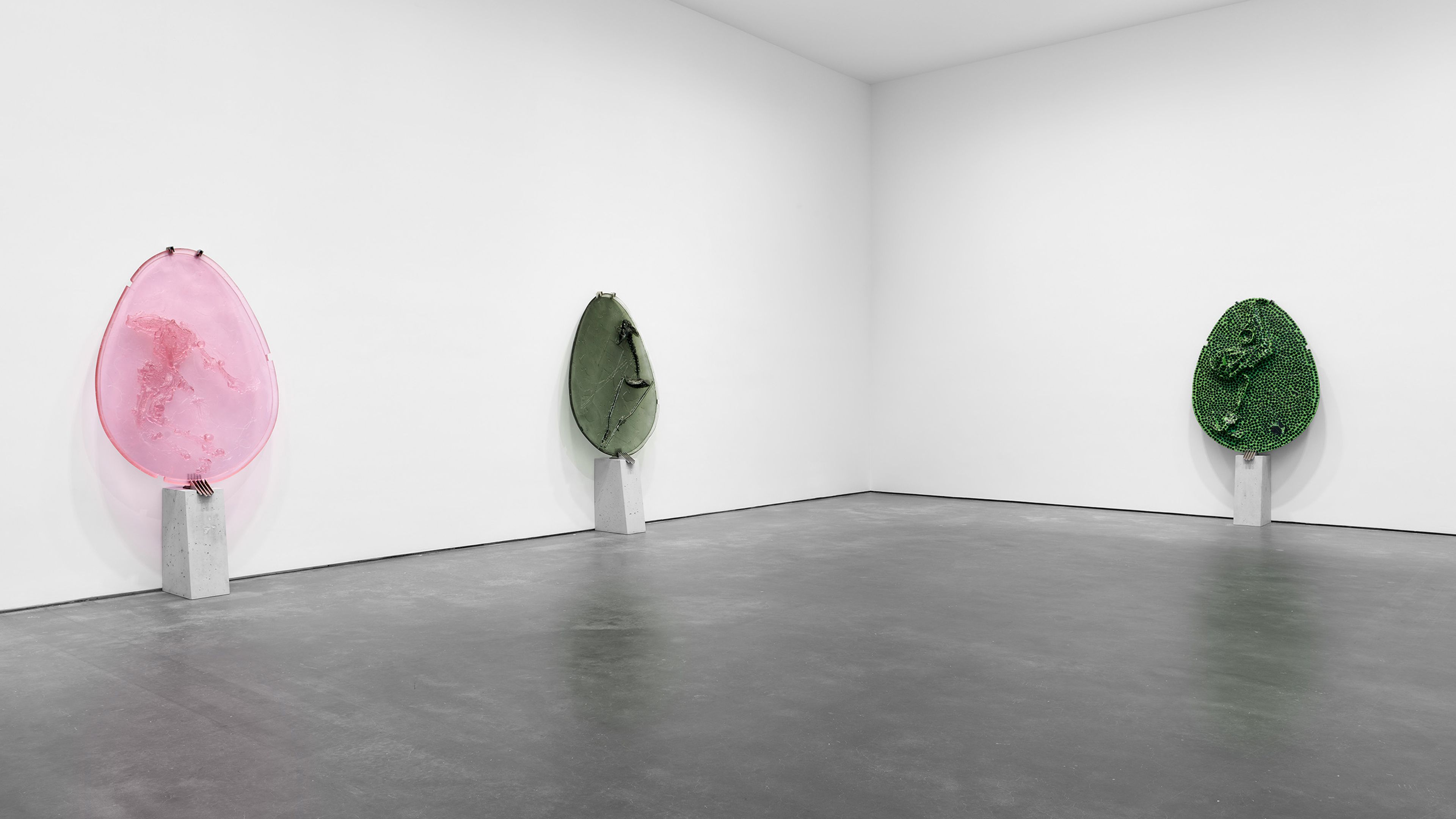

Installation views, Andra Ursuța: Retina Turner, David Zwirner, New York, 2025. Video by Pushpin Films

Past

September 10—October 18, 2025

Opening Reception

Wednesday, September 10, 6–8 PM

Opening Reception

Wednesday, September 10, 6–8 PM

Location

New York: 20th Street

537 West 20th Street

New York 10011

Artist

Explore

Explore All Works

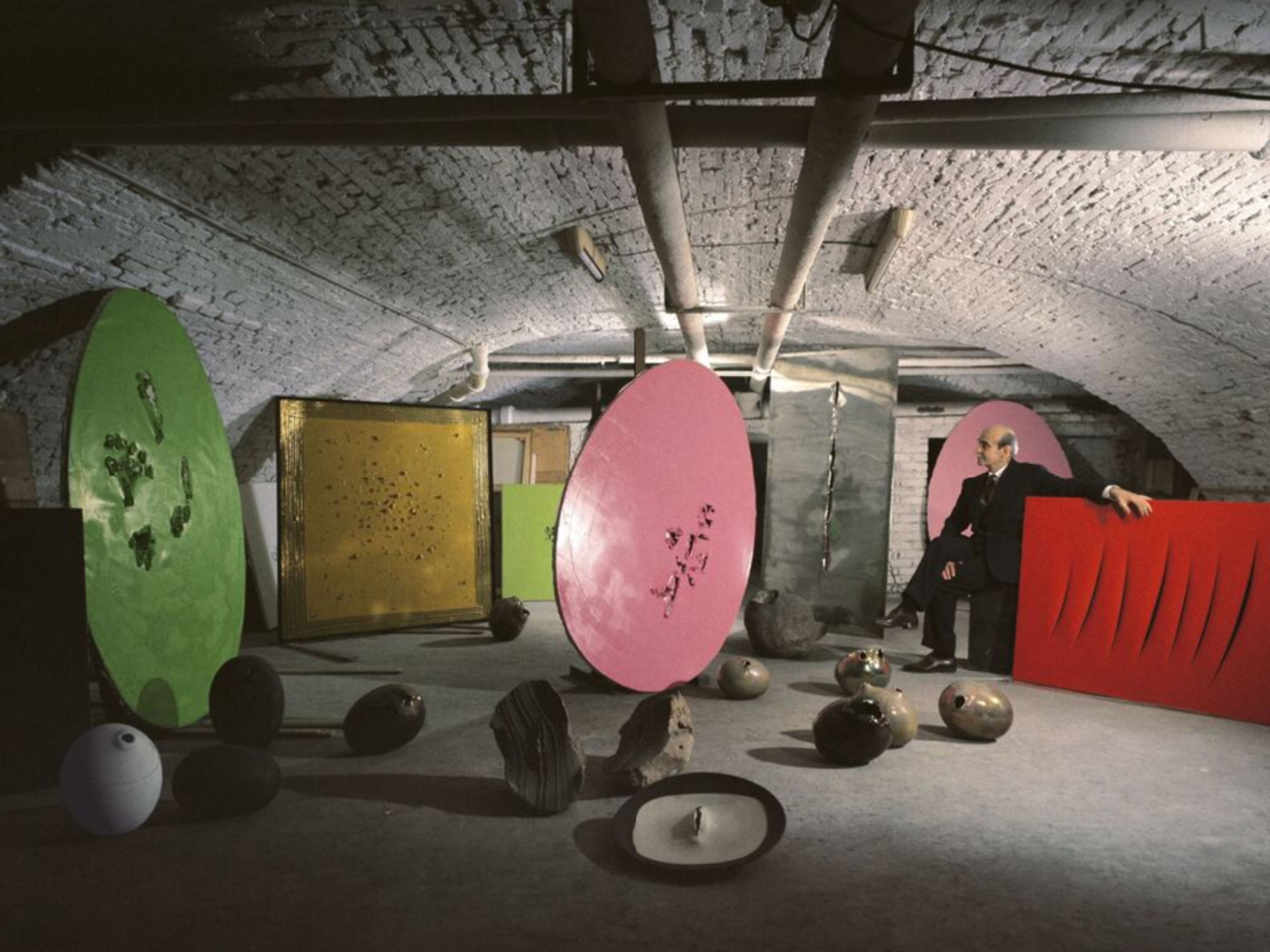

Lucio Fontana, Milan, 1963. Image: Ugo Mulas. © Ugo Mulas Heirs. Artwork: Lucio Fontana © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

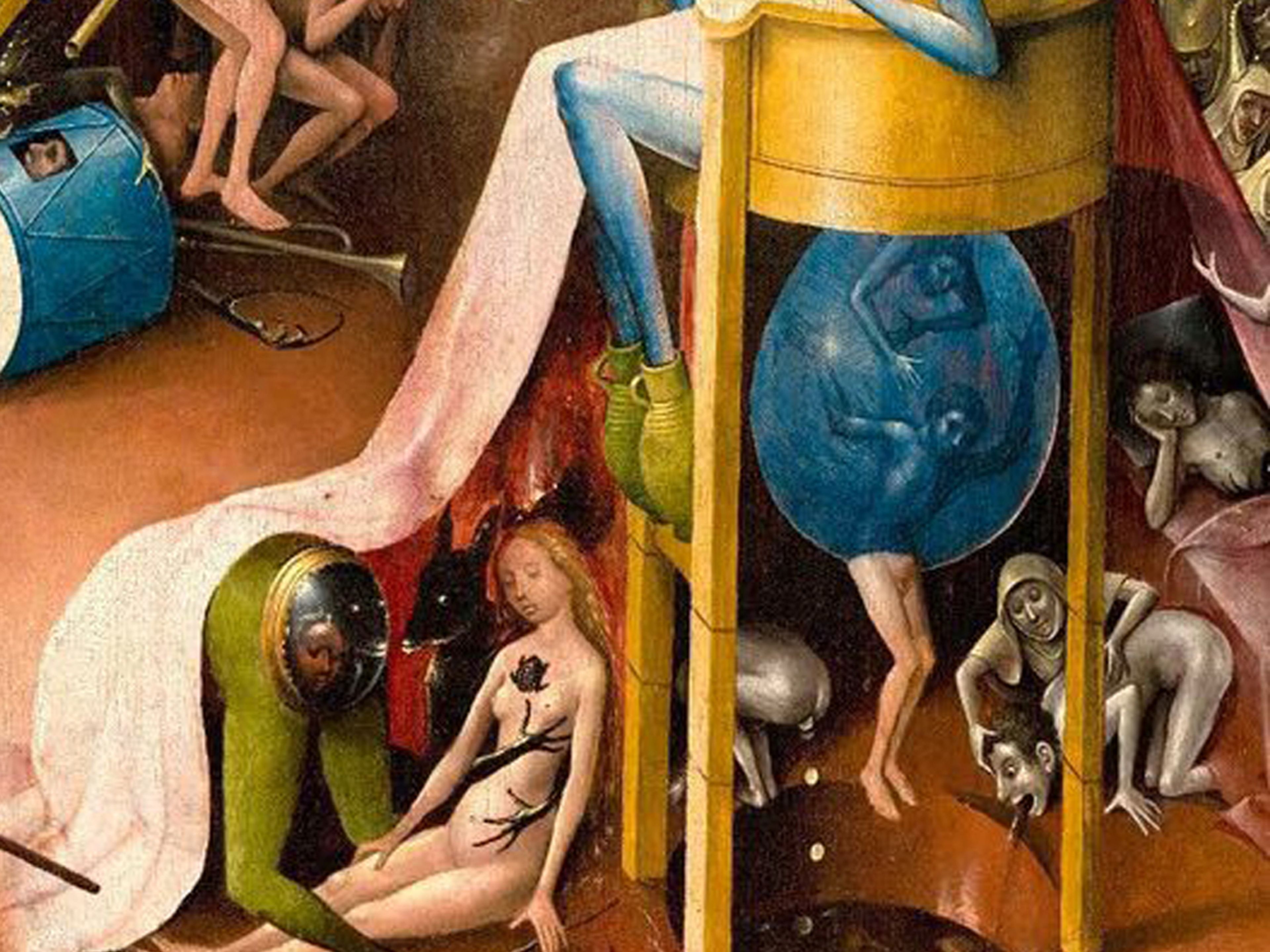

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490–1510 (detail). Collection of Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

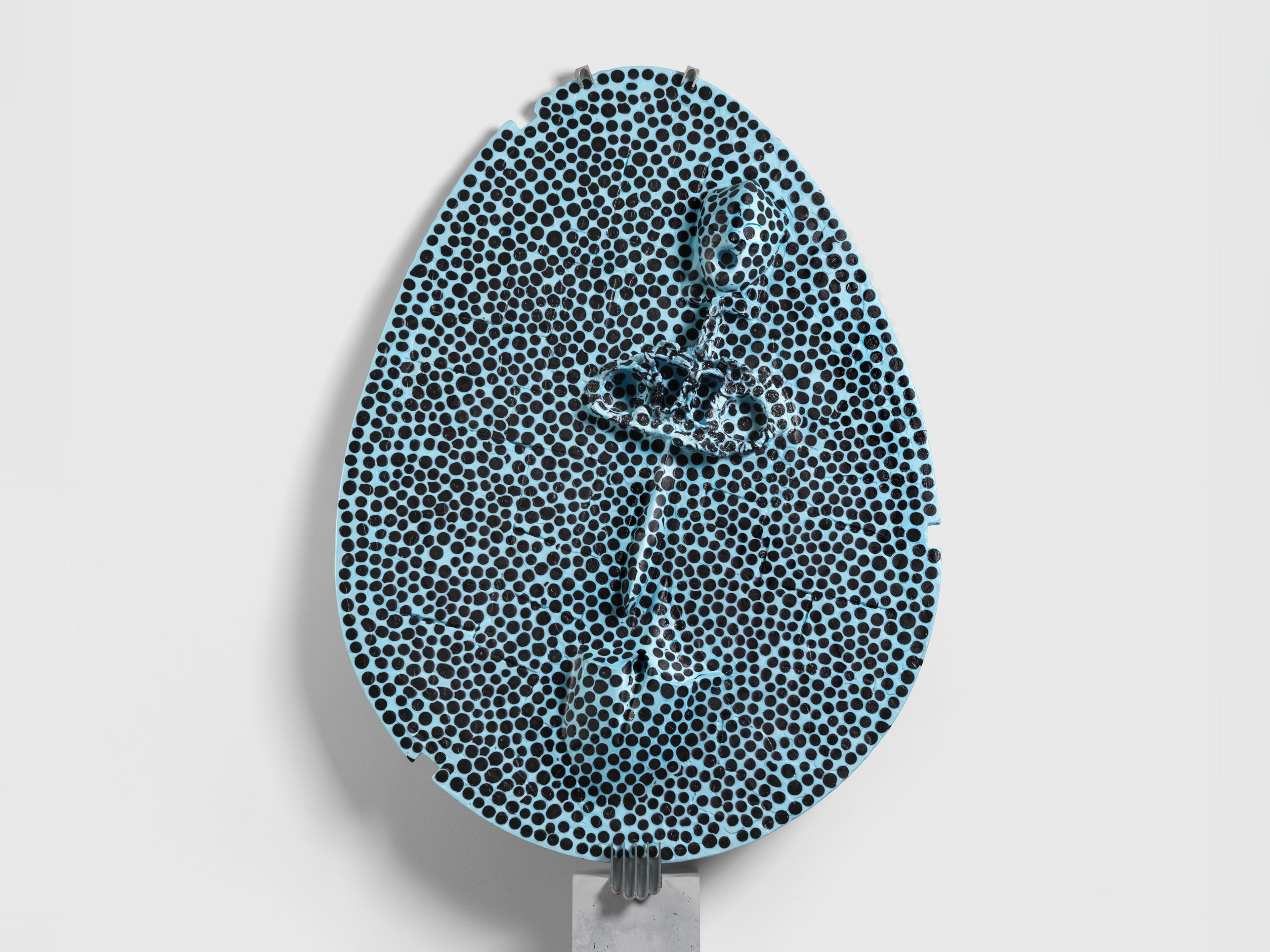

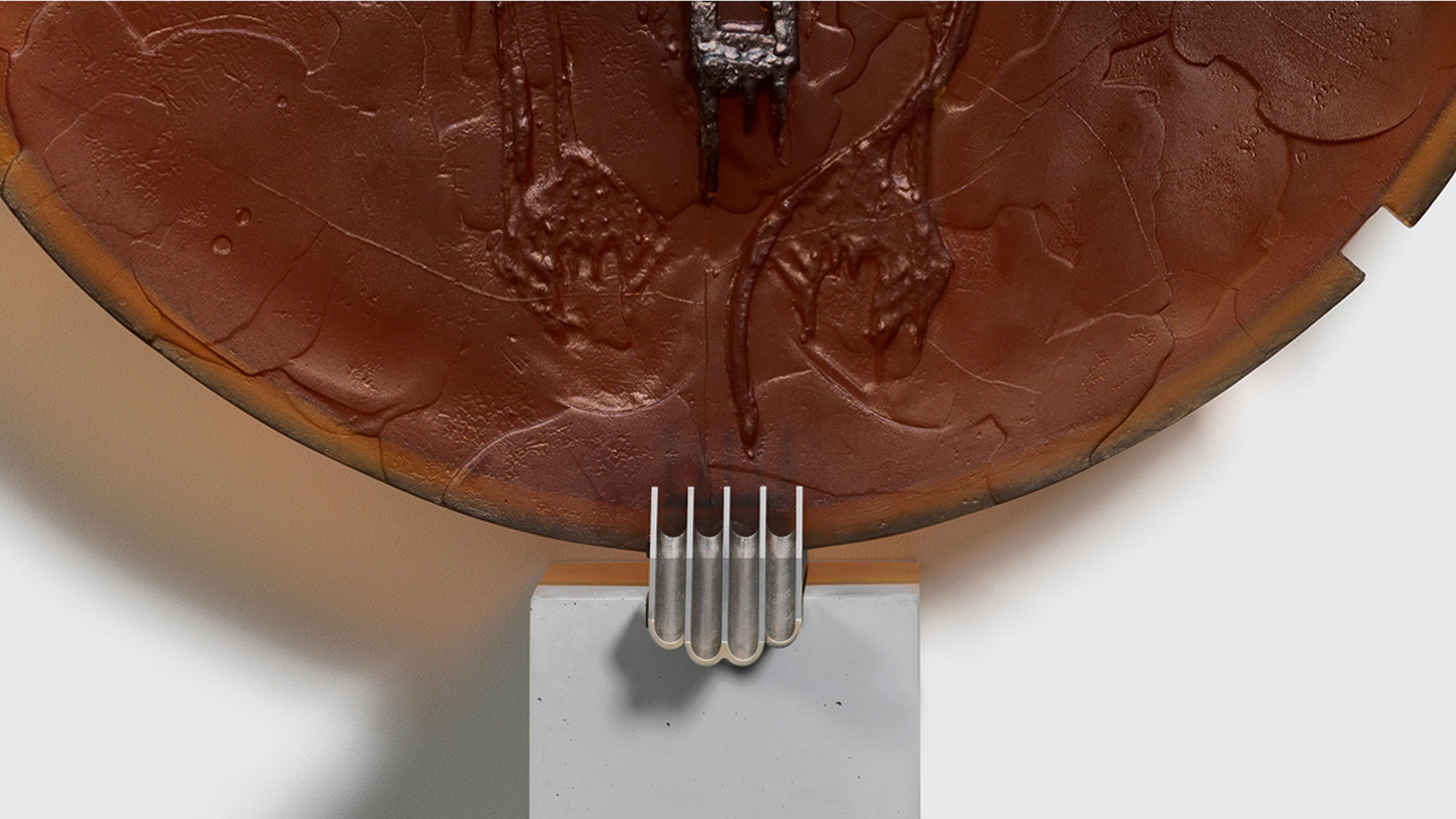

Ursuţa’s sculptures are an epilogue to Lucio Fontana’s La Fine di Dio paintings—the end of The End of God. In the 1960s, Fontana punctured egg-shaped canvases to open painting up to infinity, a gesture of optimism in an era of space exploration. Ursuţa retains the cosmic oval but inverts its meaning: where Fontana sought expansion, she shows implosion. Her panels are sealed worlds of vitreous black humor, resonating not with visions of the beyond but with the static of the image-world. They announce a culture that has retreated from the horizon of collective imagination into an endless circulation of dazzling but empty images.

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Foreskin Mince), 2025

“There is a stratification of references to the past and the future that makes Andra’s sculptures incredibly unique. There is this tension between an imagination of what is to come and a fictional construction of one’s own origins.”

—Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director, New Museum, New York

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Purple), 2025 (detail)

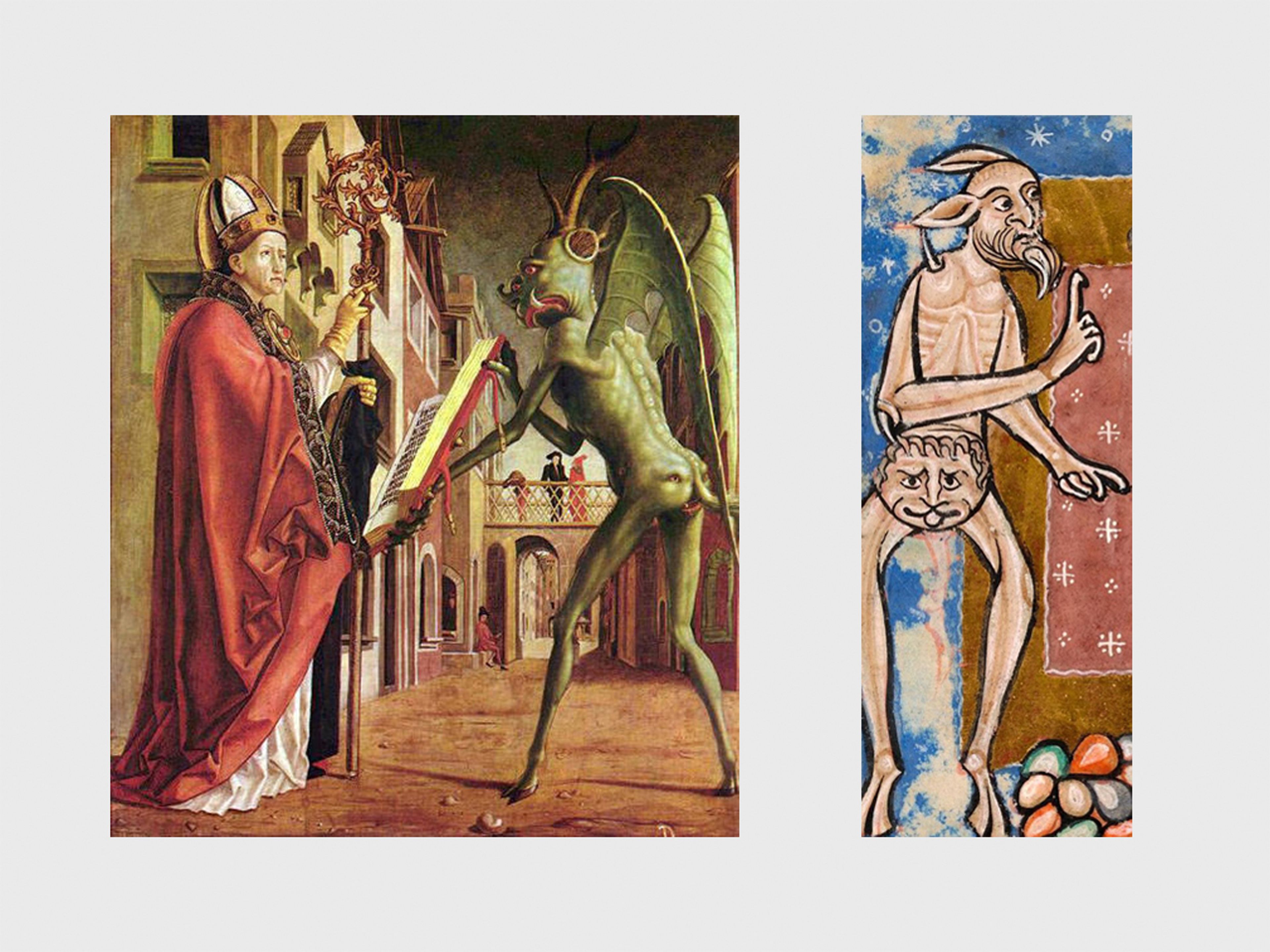

Master of Belmonte, Saint Michael, 1450–1500 (detail). Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Left: Michael Pacher, St. Wolfgang and the Devil, 1471–1475. Collection of Alte Pinakothek, Munich; right: Three Temptations of Christ, English manuscript illumination from Huntingfield Psalter, c. 1215 (detail). Collection of The Morgan Library and Museum, New York

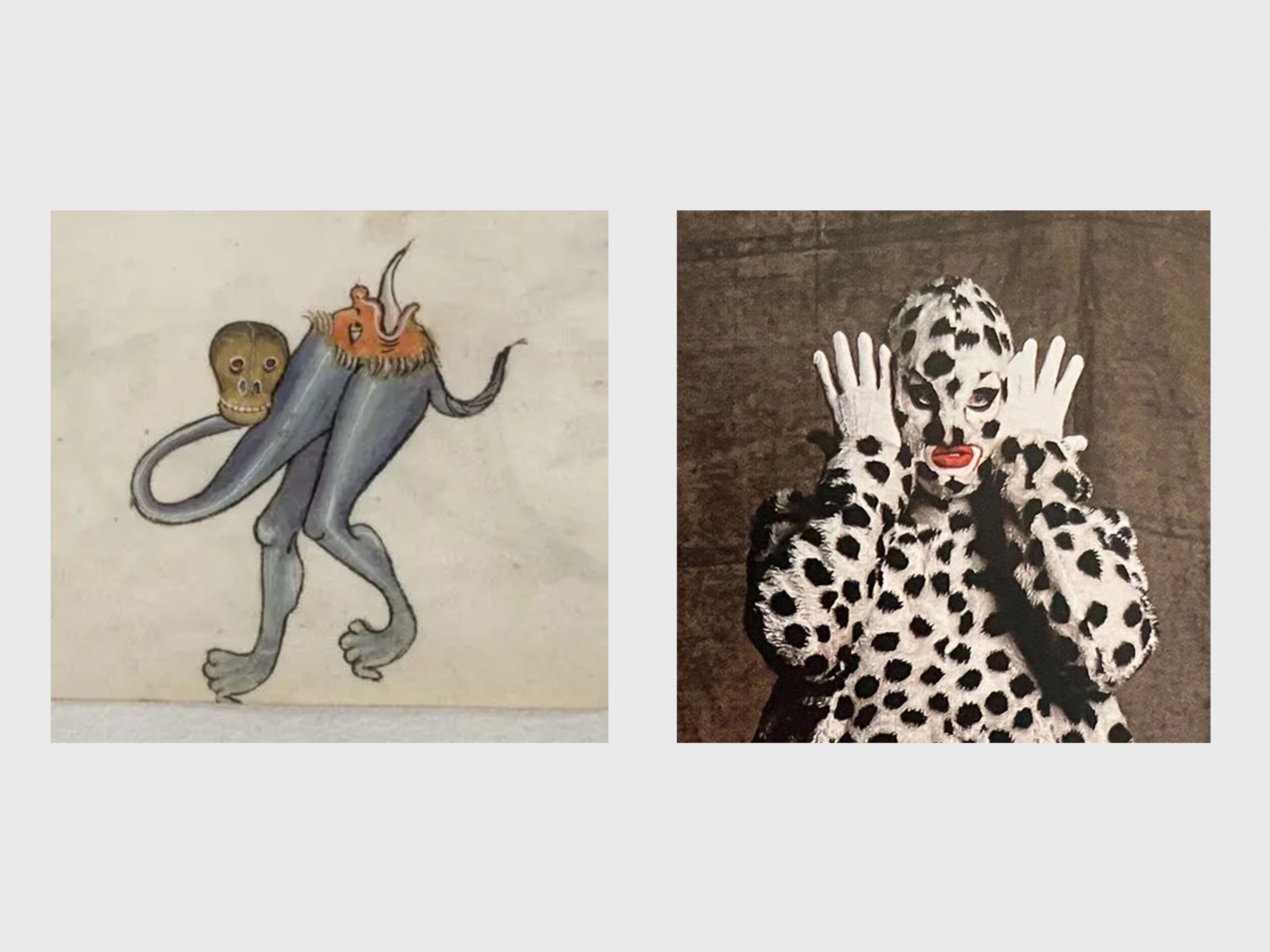

Left: Marginal decoration from the Luttrell Psalter, c. 1320-–1340 (detail). Collection of the British Library, London; right: Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery, Session I, Look 1, 1988. © Fergus Greer

The Private Dancers draw on a long tradition of imagining bodies as unstable, composite forms—at once theatrical, grotesque, and alive with artifice. The violet figure of Private Dancer (Purple) evokes the demon crushed beneath Saint Michael in the fifteenth-century painting by the Master of Belmonte, itself a composite creature made from smaller fantastical beasts. Medieval artists often rendered monsters this way: not only unholy, but literally un-whole.

With these works, Ursuța channels both high and low culture into glass, where bodies shimmer between excess and fracture, weight and fragility, their strangeness crystallized into luminous, shifting presence.

“Though her subjects are dark or, in some instances, even macabre, Ursuţa’s work never strays into histrionics of gratuitous gore. Nor does it simply traverse bleak landscapes of calamity and defeat. At its heart, her work is a study of vulnerability, resilience, and survival.”

—Natalie Bell, curator, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge

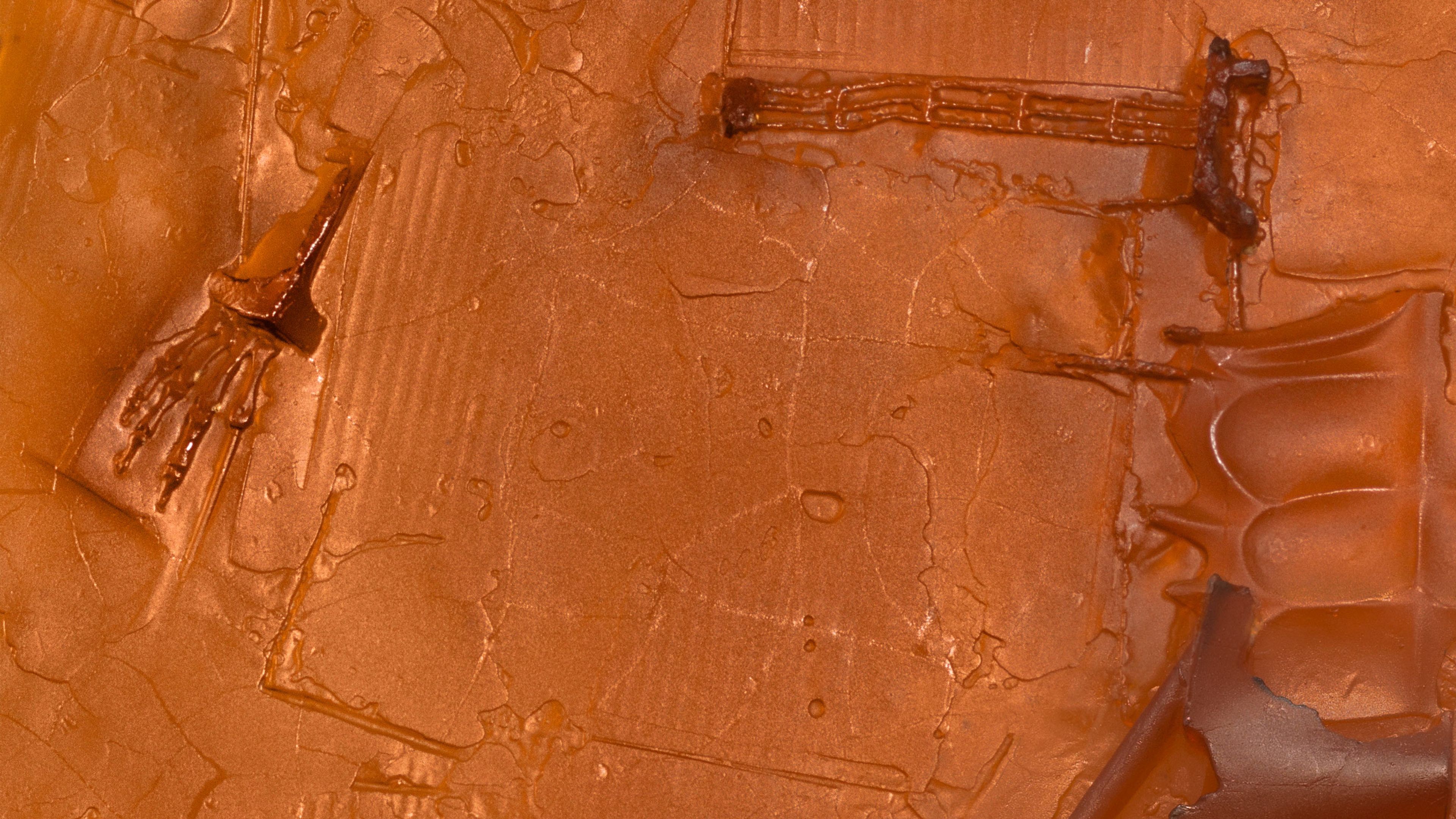

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Amber), 2025 (detail)

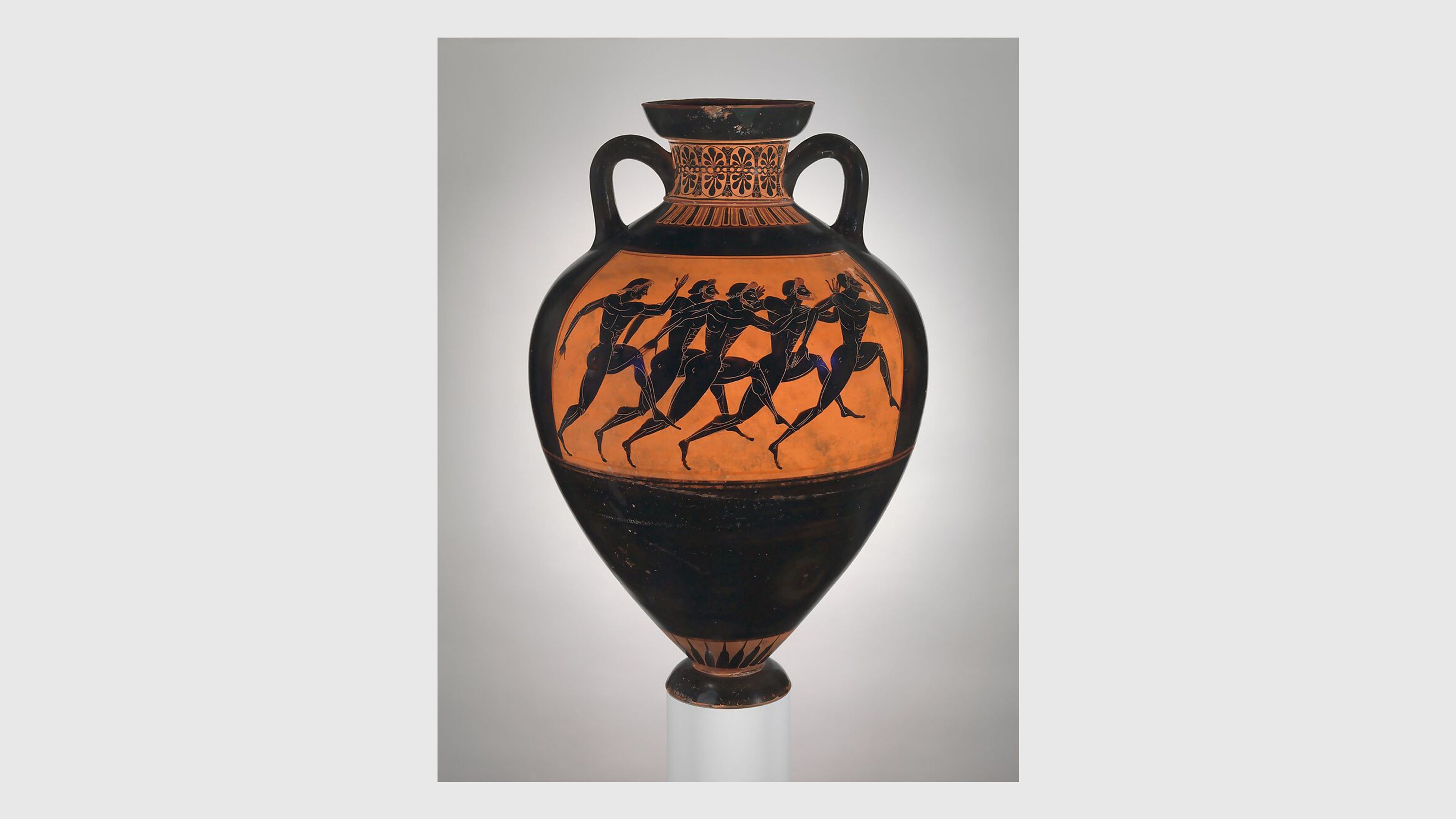

Euphiletos Painter, Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora, c. 530 BCE. Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

“Ursuţa isn’t very concerned with narrativity in her practice, and to that end she often complicates linear time by including a hodgepodge of aesthetic references.… The result is haunting yet humorous humanoid figures that refuse to be historicized.”

—Margaret Carrigan, Artnet News, 2025

Installation view, Andra Ursuţa: Retina Turner, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Pink), 2025 (detail)

Installation view, Andra Ursuţa: Retina Turner, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

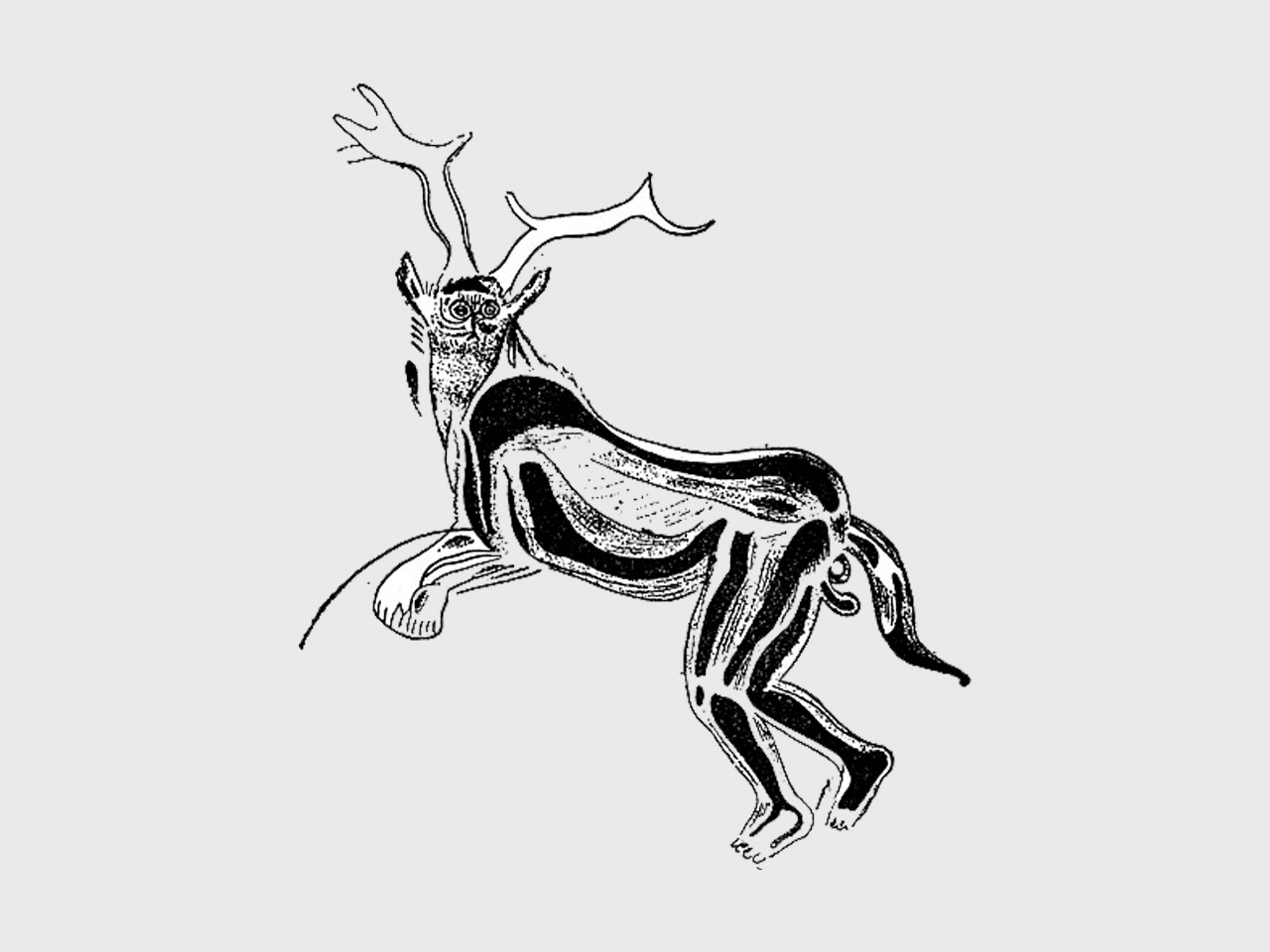

Henri Breuil, sketch of the Sorcerer, Cave of the Trois-Frères, Ariège, France, c. 13,000 BCE

This inward turn connects Ursuţa’s dancers to the origins of visual art. In prehistoric caves, depictions of animals were interlaced with grids, spirals, and dots—hallucinations produced in the darkened chamber of the eye. These earliest images fused representation with perception’s internal dream. Ursuţa renews this conjunction for a culture oversaturated with visibility: the Private Dancers are both figures and phantoms, projections of an eye that has turned inward.

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Rose), 2025 (detail)

“They reached out to their emotionally charged visions and tried to touch them, to hold them in place, perhaps on soft surfaces and with their fingers. They were not inventing images. They were merely touching what was already there.”

—David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art, 2002

Installation views, Andra Ursuța: Retina Turner, David Zwirner, New York, 2025. Video by Pushpin Films

Cast polychrome millefiori glass bowl, c. 200 BC–100 BC. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Hemispherical mould-pressed glass mosaic bowl from the Hellenistic period. © The Trustees of the British Museum

In these works, the murrine produces dense papillary fields that echo the sudden proliferation of dots across vision at the moment of a retinal tear. Each figure appears in both translucent and opaque aspects, as if vision were oscillating between clarity and obscurity. These entoptic specters are embodied floaters, phosphenes, and drifting flashes that belong to the eye rather than the external world.

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Grey Mince), 2025 (detail)

“At once seductive and unsettling, Andra Ursuța’s formally innovative sculptures … are radical hybrid beings.… [Her] work emphasises the vulnerability of the human form and the complexity of desire.”

—Madeline Weisburg, Biennale Arte 2022: The Milk of Dreams, 2022

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Burnt Raspberry), 2025 (detail)

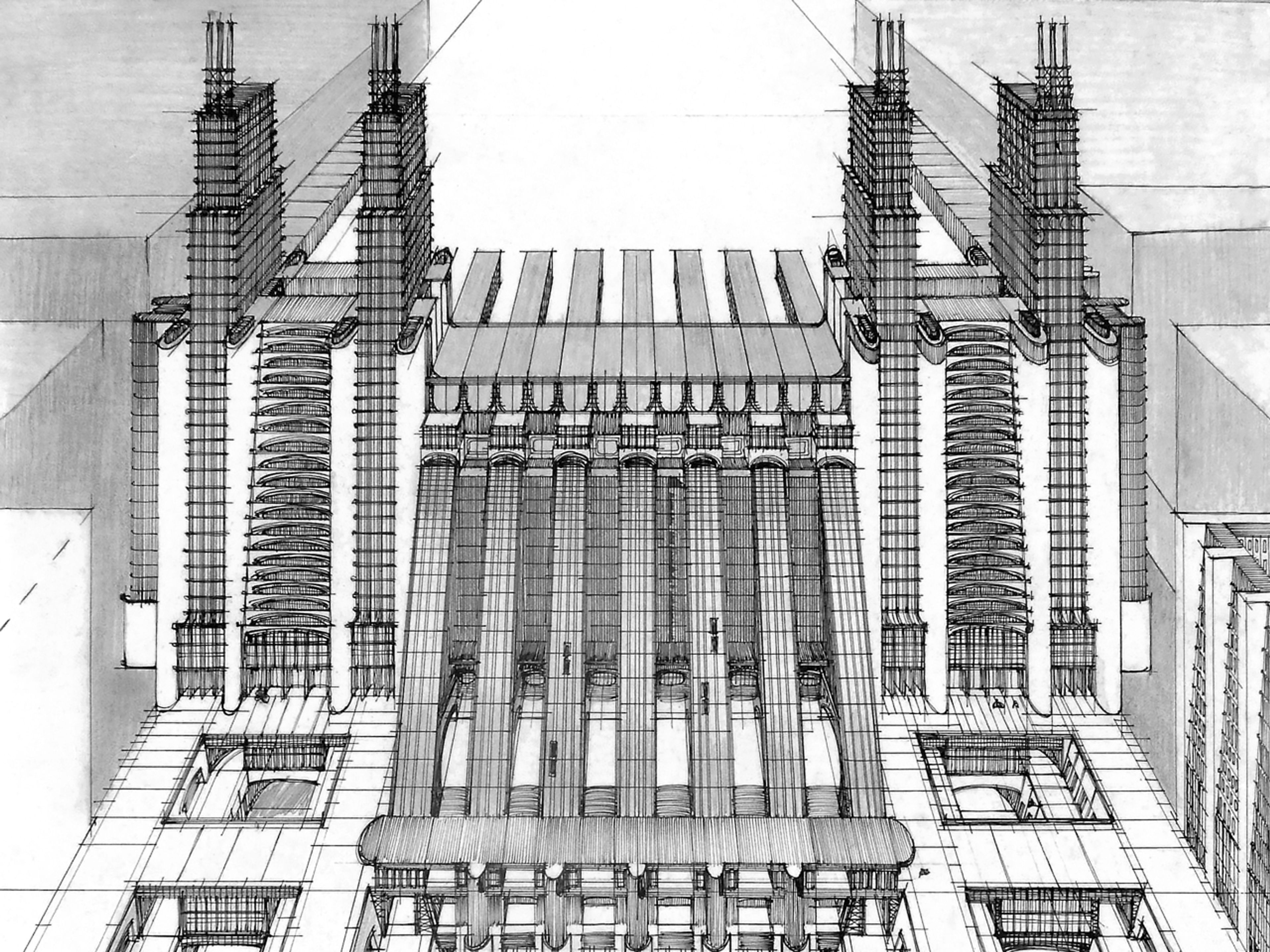

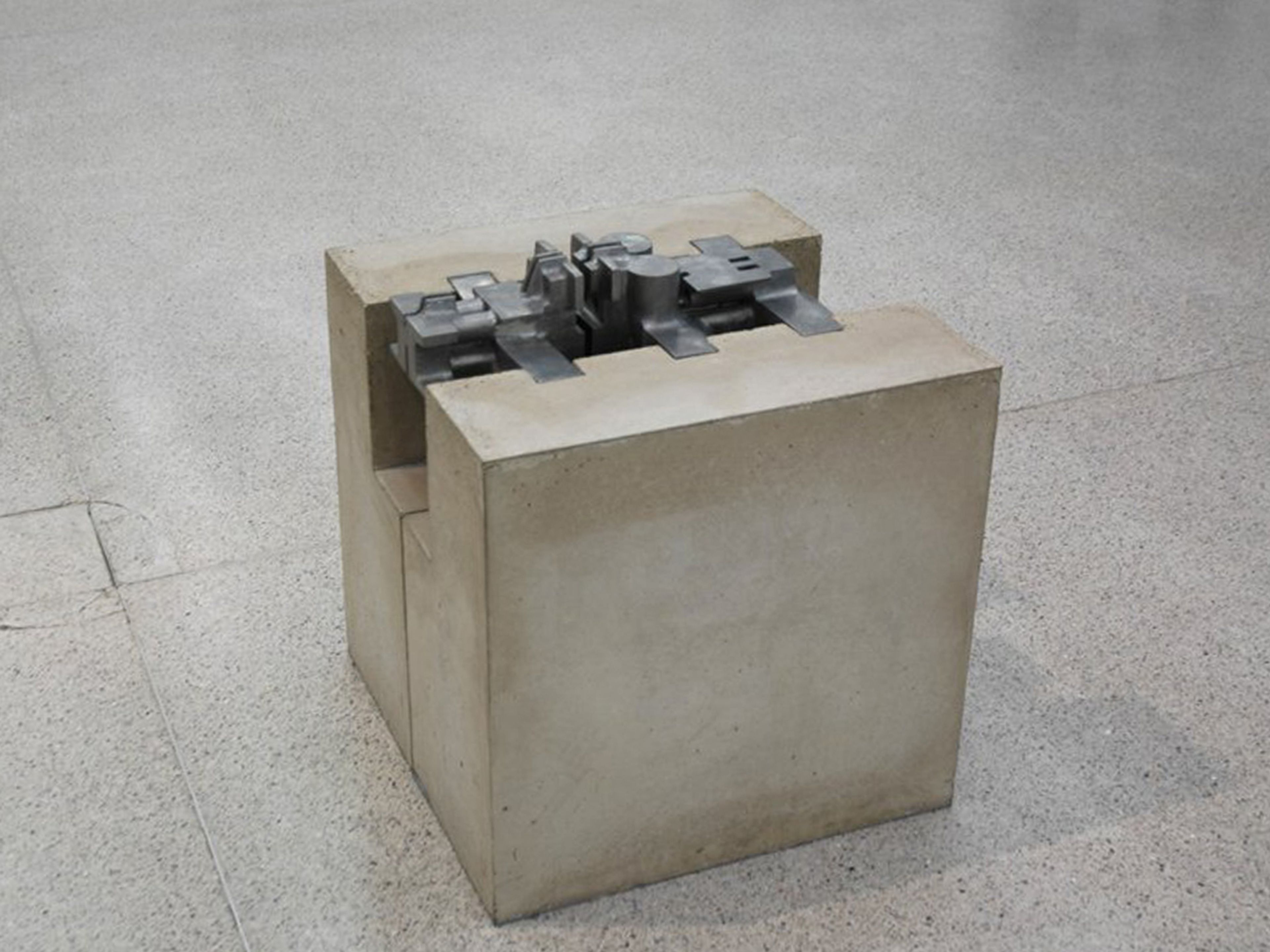

Antonio Sant’Elia, Air and train station with funicular cableways on three road levels from La Città Nuova, 1914 (detail)

Walter Pichler, Compact City, 1963. Photo by Helena Doudová

Anchored on concrete pedestals reminiscent of Italian Futurist Antonio Sant’Elia’s visionary architecture, and supported by mounting hardware that echoes Austrian architect Walter Pichler’s machine forms, Ursuţa’s precariously balanced relics eulogize vision in a world that can only show more and more but sees less and less. They commemorate not utopia but its failure.

Andra Ursuţa, Private Dancer (Peach), 2025 (detail)

“Memory, death, the human condition, and the absurdity and irony of life are all inspirations for the artist. Her work is ripe with emotion and contradictions—pathos and humor, melancholy and hope, raw and refined, hard and soft, aggressive and tender. It’s at times vulgar and political, poignant and wry, exotic and familiar.”

—Ali Subotnick, essay for Hammer Projects: Andra Ursuţa, 2014

Installation views, Andra Ursuța: Retina Turner, David Zwirner, New York, 2025. Video by Pushpin Films

Inquire about works by Andra Ursuţa